Go with the flow: What are flow batteries, and how do they work?

Go with the flow: What are flow batteries, and how do they work?

The Queensland Government’s recently announced Queensland Energy and Jobs Plan commits $500 million to grid-scale and community batteries, including flow batteries, which can be manufactured locally. But what are flow batteries, and how are they different from lithium-ion batteries?

Under the Queensland Energy and Jobs Plan, 80 per cent of the electricity used in Queensland is expected to come from renewable sources by 2035. That’s a significant increase on the 21.4 per cent that comes from renewables today.

That means there’ll be a much larger proportion of wind and solar generation in the energy grid. But the output of these generators is variable – it changes depending on the weather and the time of day.

In order for the grid to remain reliable and resilient when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing, these variable renewable energy sources need to be firmed up with dispatchable energy sources. These are energy sources that aren’t dependent on the weather, and can be ramped up quickly to cover shortfalls in supply.

A fundamental problem with electricity is that it can’t be captured and stored. But batteries are a way of getting around this problem – they store chemicals that can be converted into electrical energy, through a process known as electrochemistry. This energy can be released almost instantaneously, helping to maintain grid stability at times of peak demand.

That’s why batteries are a key component of the Queensland Energy and Jobs Plan. Under the Plan, the state’s coal-fired power stations will gradually become clean energy hubs. These hubs will be home to large, grid-scale batteries, taking advantage of the existing transmission infrastructure at these sites. Stanwell’s Tarong and Stanwell Clean Energy Hubs will be home to large, grid-scale batteries – taking advantage of the existing transmission infrastructure at these sites.

Most grid-scale battery systems are lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries. Originally used primarily for mobile applications like smart phones, tablets and laptops, Li-ion batteries made their way into electric cars in 2008, with the production of the first Tesla Roadster.

Lithium is the lightest metal, and has the highest electrode potential, which means Li-ion batteries generally offer superior energy-to-weight performance. For this reason, they’re used in most electric car makes and models.

This means that Li-ion batteries are being manufactured in ever-increasing numbers at ever-diminishing prices, which has made them an increasingly economical option for grid-scale energy storage and home energy storage alike.

But as well as Li-ion batteries, the Queensland Energy and Jobs Plan also commits funding to flow battery technologies, which can be made in Queensland with locally sourced minerals.

What is a flow battery?

Flow battery technology is not new, with one patent filed as far back as 1879, but is a relatively new entrant into the grid scale storage market.

Flow batteries have a unique design.

The more common Li-ion batteries encase all three of their main components – an anode, a cathode, and a chemical solution called an electrolyte that allows for the flow of electrical charge between them – in a cell. A Li-ion battery can contain one of these cells, or it can contain several, but the key is that all three components of each cell are encased together.

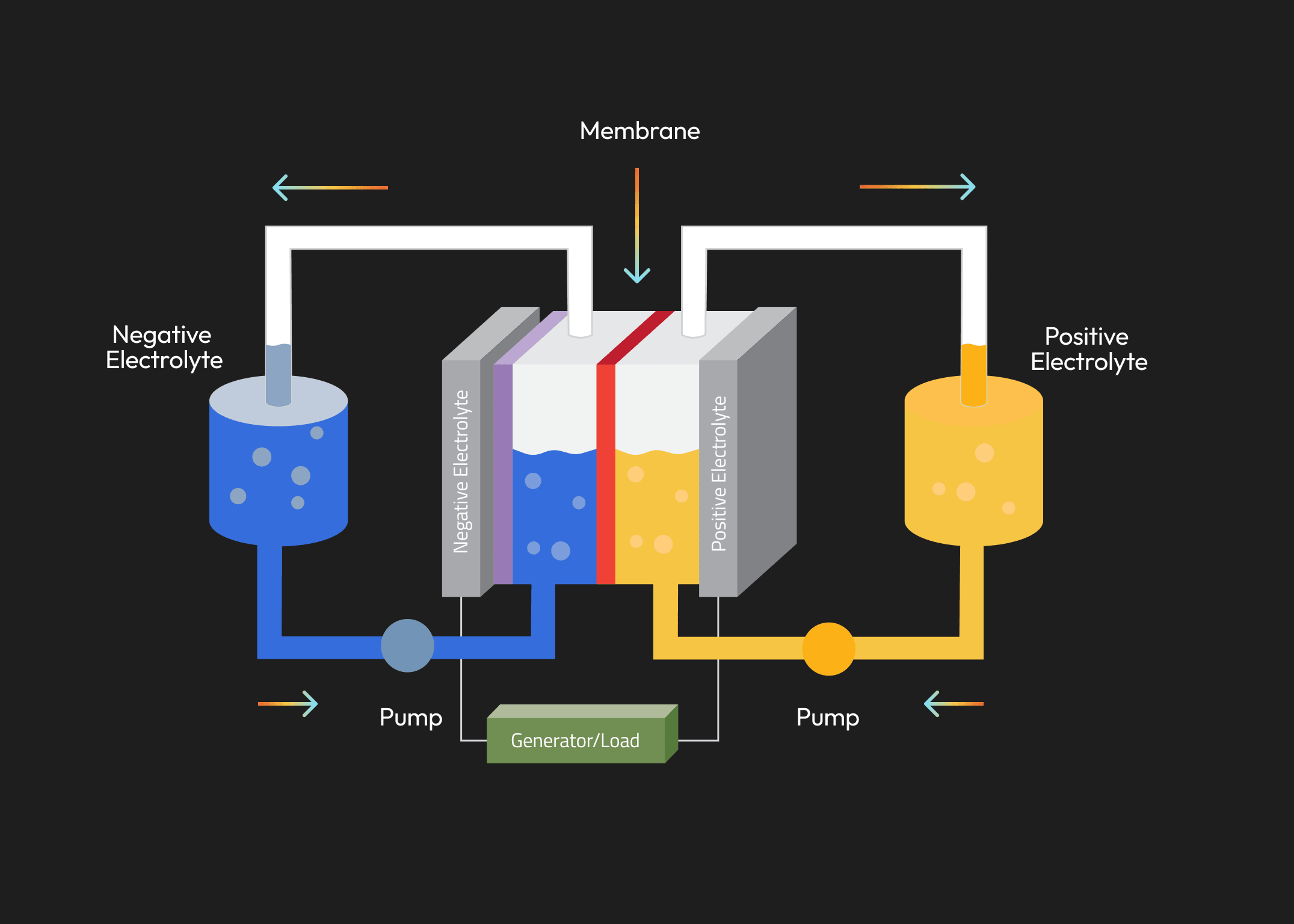

Flow batteries, however, are separated into a cell(s) and two tanks of liquid electrolyte – one tank of positive electrolyte, and one tank of negative electrolyte. The tanks are connected to a cell(s) in which the electrolytes do not mix but are separated by an ion exchange membrane. The battery is typically turned on by pumping the positive and negative electrolyte through the cell(s). During charging, electricity is applied to the cell(s) and electrolyte redox reactions take place with ion exchange through the cell membrane. Energy is “stored” in the electrolyte in the form of the changed chemical composition. During discharging, i.e. when a load is connected to the battery, electricity is ‘generated’ as the electrolyte undergoes electrochemical changes to revert towards the original uncharged state. The electricity flows in the external circuit through the load while ions are exchanged in the cells through the membrane.

The amount of electricity a flow battery can generate depends on the size of the tanks, so if you need to scale up and store more energy, you can generally swap them out for bigger tanks, without increasing the size of the cells.

There are already various types of flow batteries on the market. The difference between them is mostly in the materials that are used to make the electrolyte mixes. Australian company Redflow uses a zinc bromine electrolyte mix. Vanadium is another element used in flow batteries. Vanadium is primarily mined in China and Russia, but with 24.8 per cent of the world’s vanadium resources located in Australia, there is significant interest in mining and processing vanadium in North Queensland.

In Queensland, construction has begun in Maryborough on Australia’s first large-scale flow battery manufacturing centre. The $70 million facility, which is being developed by Energy Storage Industries – Asia Pacific (ESI), will manufacture iron flow batteries.

The electrolyte in iron flow batteries is a mix of three abundant materials – iron, salt and water.

What’s the difference between a flow battery and a lithium-ion battery?

Aside from their design, there are some important practical differences between flow batteries and Li-ion batteries.

Whereas grid-scale Li-ion batteries can usually only supply electricity to the grid for a maximum of four hours, flow batteries offer a longer duration. ESS, the Oregon-based company that developed the iron flow battery technology used by ESI, says its batteries can supply electricity to the grid for up to 12 hours at a time.

On the other hand, flow batteries tend to have much lower power density than Li-ion batteries – so while flow batteries can deliver a consistent amount of energy for a longer period of time, Li-ion batteries are better suited to providing larger bursts of energy for shorter periods of time.

Because flow batteries have a lower energy density than Li-ion batteries, they aren’t appropriate for use in electric vehicles.

Flow batteries don’t yet have a comparable commercial track record, although flow batteries, with their abundant materials, may help to bridge the gap.

Flow batteries are expected to have a longer service life than Li-ion batteries. ESS says its iron flow systems have a 25-year service life, whereas most Li-ion batteries last about 7-to-10 years.

And because flow batteries store their energy in a non-flammable liquid electrolyte in tanks exterior to the cells, they are generally considered to be safer than Li-ion batteries, which have flammable electrolyte stored in each cell.

However, those exterior tanks also mean that flow batteries tend to take up more space than Li-ion batteries, which are lighter and more portable. Not only are the tanks themselves sizable, but they have pumps, piping and cooling systems that require more maintenance than self-contained Li-ion batteries.

Ultimately, there won’t be one magic bullet – or, in this case, magic battery – that fulfills every energy storage need.

ESI’s Maryborough iron flow battery manufacturing facility sits alongside a suite of announcements from the Queensland Government, including a $15 million commitment to scale up Brisbane’s National Battery Testing Centre, and $5 million to finalise and release a Queensland Battery Strategy later this year. Stanwell and ESI have also partnered on an iron flow battery pilot project at Stanwell’s Future Energy Innovation and Training Hub.

Li-ion and flow batteries alone won’t provide all of the firming the grid needs – but alongside other energy storage technologies, like large-scale pumped hydro and gas-fired peaking plants, they can help to allow more wind and solar power to be connected to the grid, and ensure Queenslanders are provided with clean, reliable and affordable power for generations to come.

Subscribe to our newsletter

STANWELL SPARK

Stay up to date with quarterly news from Stanwell, delivered straight to your inbox. Learn more about our projects, partnerships and how we're delivering affordable, reliable and secure electricity for Queensland.